Investing in Property: Why You Can’t Save Your Way to First Home Ownership

In today’s environment, how are we to afford our first home? Are traditional methods – earning an in...

Dean Anderson

27 September 2021

Property investment has been the darling of New Zealanders, enabling and driving personal wealth for at least the past 2 generations. Literally while sleeping, houses have been increasing in value faster than inflation. However, we say that houses are now a bad investment.

For the record, our products at Kernel are not the panacea, we are not paid or paying for our opinion, we don’t hate property, banks, or any type of asset (they all have their place) but we do want to help you understand wealth creation and some of the tricks previously reserved for the rich.

We all need to live somewhere and taking out a mortgage provides three key wealth creation benefits. First a mortgage is “forced savings” – normally a table loan schedule, which if you don’t comply with and make the payments, the bank will foreclose on you. This way, you build wealth by paying down the principal of the loan little by little, regardless of capital gains.

Second, it is inexpensive leverage, because through a mortgage you can own an asset worth multiples more than your deposit, paying a lender a changing rate of interest which you can fix for periods for the certainty.

Third, houses are illiquid and difficult to divide. You can’t easily sell a portion of your house and selling takes time and costs money. This is a good thing so that we don’t rashly sell or buy in the heat of the moment, although you do hear the occasional story of an impulse auction purchase, creating a variety of consequences.

Property is a valuable asset when, excluding the main home, it is part of a well-diversified investment portfolio. Historically, it has low correlations to bonds and shares. However, in our financial advisers’ experience, people generally don’t count the total cost of ownership. They make assumptions that the property will be tenanted 52 weeks of the year, forget about property management costs, repairs and maintenance and taxes. Mainly people forget about their time involved.

Have you ever wondered why there are no large property syndicates or listed property trusts (REITs) owning residential property? It’s just not viable, even at scale. As a result, we have a country of amateur landlords.

Recent NZ Herald research suggests that almost 40% of New Zealand’s 1.9 million properties are owned by amateur landlords. Some ‘lords loudly proclaim how well they have done, and others quietly worry about their tenants and their return on investment.

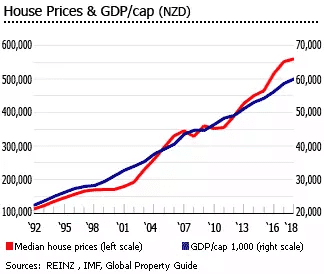

But now, four main factors have also played out. Interest rates at an all-time low, building costs remain high, landlord obligations and tenant rights are being challenged, and rents as a percentage of tenants’ income are in many areas at a maximum. New Zealand residential property prices are some of the highest in the world relative to affordability and now trending well above GDP per capita. Sure we could go further – with the likes of negative interest rates, legislation change or slum living conditions. But will this occur?

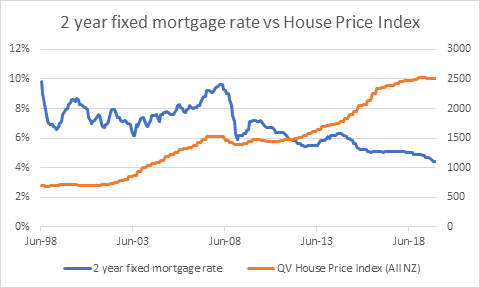

Leverage is a double benefit or double whammy. While interest rates are falling, it is a multiplier on increases in value and as the chart below shows, interest rates on mortgages have been falling for 20 years now. But what if interest rates rise?

Mortgage payments increase and property will often fall in value, leaving some leveraged investors “upside down” – owing more than the value of the asset.

This is where the concept of debt servicing is good to know. If your interest rate rose by 1%, 2%,3%, or even back to a long run average of 8%, would you be bankrupt? Or are you relying on the Reserve Bank or banks considering it too big to fail?

Now we are not suggesting interest rates are about to rise, evidence is to the contrary for the foreseeable future. However, we also don’t believe in crystal balls and suggest it is good risk management to consider the impact on you if they did.

One argument pro-property is that because of strong immigration, arduous consent processes and costs of construction, New Zealand has a shortage of houses, meaning that the houses we have are more valuable and in demand.

Infometrics modelling suggests that New Zealand might have a housing shortage of around 40,000 but overall the nationwide undersupply of housing might be as low as 2,500 dwellings. The difference is that there is oversupply of housing in parts of New Zealand, notably Christchurch, and undersupply in other parts, for example, Auckland.

The reason for the “might” is a heavy dependence on a key assumption about the number of people per dwelling, which is rising in Auckland and falling elsewhere. Simplistically, whether driven culturally, socioeconomically, both or otherwise, there are less empty bedrooms in Auckland. There is plenty of misinformation, and suffice to say it is a complex issue when you consider global trends of urbanisation, freedom of movement, and government policies such as regional development and the defunct KiwiBuild.

Additionally, there are demographic effects such as longevity, dual incomes and starting families later, making correlation between house price changes in over supplied and under supplied areas hard to identify to prove the point. Meanwhile MBIE (2019) found no evidence that a higher share of new (international) immigrants in an area is associated with higher house prices.

Both Ireland and the US experienced a significant house correction around 2008. These were due to serious structural issues: in Ireland around construction addiction creating a “bullwhip effect” of oversupply and in the US with subprime mortgages allowing huge leverage relative to wealth and income.

Both these bubbles burst. However, short of interest rate rises driven globally, our RBNZ macro-prudential policy looks to learn from the past, and due to the concepts of loss aversion and anchoring, few vendors are prepared to sell at a loss, instead holding on until growth returns. These factors smooth the property market falls, as seen in New Zealand twice in the last 20 years with the plateau of prices. If we look at the below graph as visual evidence, you could argue we are due for a plateau again, despite falling interest rates.

It is an understatement to say landlords are historically lightly regulated and that legislation has favoured the owners over the occupiers in New Zealand. However, the Healthy Homes Guarantee Act passed in 2017 introduced standards to improve the quality of rental housing in New Zealand. These obligations on landlords stagger in until 2024 and increase maintenance costs. Furthermore, there are proposed changes to the Residential Tenancies Act 1986 which aim to increase tenant’s rights and stability. According to the 2018 census, 55% of Auckland adults and 48% nationally are not owning their own home, and this long term trend away from home ownership, surely will continue to increase the voting power of tenants and government’s promises for election, towards the international standards seen in other developed countries. Not a trend of increasing regulation and cost we would be betting against anyway.

Both have their pros and cons and the ‘best investment’ is the one that is most right for the individual investor at the time, based on their risk profile, wider asset base, cash generating ability and longer term goals. Long term in NZ and elsewhere, the stock market performs best.

The table below summarises the often overlooked advantages and disadvantages. Aside from leverage, we would say managed funds are better long term wealth creation.

Managed funds: | Residential rental property: |

|---|---|

Historically shown the best growth over the long term in NZ | Historically shown good growth over the long term in NZ |

Potential for huge diversification into sectors, economies and using different fund managers. | Harder to be adequately diversified. Even if you have multiple rental properties, they are usually in same city. |

Ease and speed to sell – can receive cash without a discount to value usually within a week. | Slow to sell. From decision to settlement is usually months. |

In New Zealand, it’s not easy to leverage, “margin” accounts are not common. | Banks are willing to lend against it so easy to leverage the investment i.e. mortgages. |

Low transaction costs < 1% value | High transaction costs ~4% of value if including advertising and conveyancing. |

Very little time commitment by you. A professional is managing the investment on your behalf and this cost is built into the managed fund. | Ownership burden, tenants, property management time and/or cost. Repairs, maintenance, upkeep, risk of damage. |

Ability to use PIE or other tax structures, to reduce the tax payment. Normally no need for a tax return. | Rental income declared as personal income. Can offset expenses against income. Annual at minimum requirement for tax return and accounting. |

No capital gains tax. | Capital gains tax if sold within 5 years. |

A number of regulatory checks and balances including manager licensing, supervisor and a custodian. The manager must follow what is contained in the Product Disclosure Statement | Burden on the vendor and purchaser for legal risk, warranties and indemnities. |

Excluding impact of leverage, shares have historically outperformed all other asset classes over the long term. | Historically it has been perceived to be less volatile than shares. |

Because considered non-unique, accurate valuation available every minute. Move with sentiment causing emotional biases. | Because considered unique, valuation only on sale or inaccurate by a valuer. Self-valuation as sentiment. |

Good regular income possibilities above term deposits. | Net (of costs) income usually low. It is more of a speculation purchase for capital gain rather than for regular income. |

Can start with $100 | Difficult to start with less than $100,000 |

Not to mention further economic concepts or moral issues such as unproductive assets, lifetime of debt, deviation from inflation and real GDP, and improving quality of housing.

So to summarise, we suggest that property is now a bad investment, because 1) mortgages rates driving the past 20 year trend are unable to fall much further, 2) we are likely due for a plateau or underperformance in the next 3-5 years, 3) affordability is low inhibiting gross rental increases, and 4) landlord regulation and tenant rights are likely to increase.

But we would say that, what do you think?

Investing in Property: Why You Can’t Save Your Way to First Home Ownership

In today’s environment, how are we to afford our first home? Are traditional methods – earning an in...

Dean Anderson

27 September 2021

How to Invest A Lump Sum of Money

If you're wanting to invest a lump sum of money - how best do you do this? We explain when you shoul...

Stephen Upton

18 November 2024

How Do I Choose the Right Investment Strategy for Me?

Without an investment strategy, how do you know whether you'll meet your short, medium and long term...

Chi Nguyen

19 January 2022

For market updates and the latest news from Kernel, subscribe to our newsletter. Guaranteed goodness, straight to your inbox.

Indices provided by: S&P Dow Jones Indices